Comprehensive Fit Example with Crossed-Random Effects

Comprehensive-Fit-Example-with-Crossed-Random-Effects.RmdWe begin the analysis by loading mptstan. We then use

options() to auto-detect the numbers of cores and ensure

fitting uses multiple cores.

library(mptstan)

options(mc.cores = parallel::detectCores())We show the analysis of a recognition memory data set (from Singmann,

Kellen, & Klauer, 2013) using the unsure-extended 2-high threshold

model to a dataset investigating the other-race effect (i.e., a study

with two different types of old and new items, own-race faces and

other-race faces). This data is available in mptstan as

skk13. We will analyse this data using crossed-random

effects for participants and items.

str(skk13)

#> 'data.frame': 8400 obs. of 7 variables:

#> $ id : Factor w/ 42 levels "1","3","5","6",..: 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 ...

#> $ trial: Factor w/ 200 levels "1","2","3","4",..: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 ...

#> $ race : Factor w/ 2 levels "german","arabic": 2 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 1 1 ...

#> $ type : Factor w/ 2 levels "old","new": 1 1 2 2 1 1 1 1 2 2 ...

#> $ resp : Factor w/ 3 levels "old","unsure",..: 3 1 3 1 1 1 3 1 3 3 ...

#> $ rt : num 4.68 2.75 4.25 1.6 0.95 ...

#> $ stim : Factor w/ 200 levels "A001","A002",..: 40 132 117 143 140 162 193 19 120 170 ...Because we want the MPT model parameters to differ across the

race factor in the data (i.e., the race of the

to-be-recognised face), we set contrasts appropriate for Bayesian models

for the current R session using

options(contrasts = ...). In particular, we use the

contrasts proposed by Rouder et al. (2012) that guarantee two things:

(a) contrasts sum to zero: for each factor/coefficient, 0 corresponds to

the mean value and not to a specific factor level. Consequently, these

contrasts are appropriate for models that include interactions. (b)

contrasts have the same marginal priors for each factor level. These

priors are available in package bayestestR as

contr.equalprior. (Note that setting contrasts using

options() affect most regression functions in

R, such as lm and lmer.)

library("bayestestR")

options(contrasts=c('contr.sum', 'contr.equalprior'))Step 1: Create MPT Model Object

The first step when using mptstan is the creation of a

MPT model object using make_mpt() (which creates an object

of class mpt_model).

make_mpt() can read MPT models in both the commonly used

EQN model format (e.g., used by TreeBUGS) and

the easy format introduced by MPTinR.

# For the easy EQN format, we just need the EQN file location:

EQNFILE <- system.file("extdata", "u2htm.eqn", package = "mptstan")

u2htsm_model <- make_mpt(EQNFILE) ## make_mpt() auto-detects EQN files from name

#> model type auto-detected as 'eqn'

#> Warning: parameter names ending with a number amended with 'x'

u2htsm_model

#>

#> MPT model with 4 independent categories (from 2 trees) and 4 parameters:

#> Dn, Do, g1x, g2x

#>

#> Tree 1: old

#> Categories: old, unsure, new

#> Parameters: Do, g1x, g2x

#> Tree 2: new

#> Categories: old, unsure, new

#> Parameters: Dn, g1x, g2x

## Alternatively, we can just enter the equations and use the easy format.

u2htm <- "

# Old Items

Do + (1 - Do) * (1 - g1) * g2

(1 - Do) * g1

(1 - Do) * (1 - g1) * (1 - g2)

# New Items

(1 - Dn) * (1 - g1) * g2

(1 - Dn) * g1

Dn + (1 - Dn) * (1 - g1) * (1 - g2)

"

# for the easy format, we need to specify tree names and category names

u2htsm_model_2 <- make_mpt(text = u2htm,

trees = c("old", "new"),

categories = rep(c("old", "unsure", "new"), 2))

#> Warning: parameter names ending with a number amended with 'x'

u2htsm_model_2

#>

#> MPT model with 4 independent categories (from 2 trees) and 4 parameters:

#> Dn, Do, g1x, g2x

#>

#> Tree 1: old

#> Categories: old, unsure, new

#> Parameters: Do, g1x, g2x

#> Tree 2: new

#> Categories: old, unsure, new

#> Parameters: Dn, g1x, g2xAs shown in the output, if a model parameter ends with a number,

mptstan adds an x to the parameter name (as

brms cannot handle custom parameters ending with a number).

If a model already has a parameter with this name (i.e., the original

parameter name ending with a number plus x) this might leave to problems

and should be avoided.

Step 2: Create Formula (Optional)

The second and optional step is creating an MPT formula object with

mpt_formula(). Here, we show the case in which the same

formula applies to all MPT model parameters. In this case, we specify

only a single formula and also need to pass the MPT model object (as the

model argument).

In the formula, the left-hand-side specifies the response variable

(in the present case resp) and the right-hand side

specifies the fixed-effect regression coefficients and random-effect

(i.e., multilevel) structure using the brms-extended

lme4 syntax. Here, we have one fixed-effect, for the

race factor. Furthermore, we have both by-participant and

by-item random-effect terms. For the by-participant random-effect term

we estimate both random intercepts and random slopes for

race (as race is a within-participants

factor). For the by-item random-effect term we only estimate random

intercepts. For both random-effect terms we add a unique identifier

between the regression structure for the random-effect term (i.e.,

race or 1) and the grouping factor (i.e.,

id and stim), p for participants

and i for items. These identifiers ensures that

random-effect correlations are estimated across MPT model parameters. In

other words, these identifiers ensure that for each random-effect term

the full correlation matrix across all MPT model parameters is estimated

in line with Klauer’s (2010) latent trait approach.

u2htm_formula <- mpt_formula(resp ~ race + (race|p|id) + (1|i|stim),

model = u2htsm_model)

u2htm_formula

#> MPT formulas for long / non-aggregated data (response: resp):

#> Dn ~ race + (race | p | id) + (1 | i | stim)

#> Do ~ race + (race | p | id) + (1 | i | stim)

#> g1x ~ race + (race | p | id) + (1 | i | stim)

#> g2x ~ race + (race | p | id) + (1 | i | stim)As shown in the output, if we specify a MPT model formula with only a

single formula, this formula applies to all MPT model parameters. In

this case, using mpt_formula() is optional and we could

also specify the formula as the first argument of the fitting function,

mpt().

Creating a formula object is not optional if you want to specify an

individual and potentially different formula for each MPT model

parameter. In this case, the left-hand-side of each formula needs to

specify the MPT model parameter and the response variable needs to be

specified via the response argument. For examples, see

?mpt_formula.

Step 3: Fit Model

With the MPT model object and model formula we are ready to fit the

MPT model. For this, we use function mpt() which in

addition to the two aforementioned objects requires the data as well as

the variable in the data distinguishing to which tree (or data type) a

particular response belongs. In the present case that is the

type variable. (The tree variable can only be omitted in

case the model consists of solely one tree.)

In addition to the required arguments (model object, formula, data,

and tree variable), we can pass further arguments to

brms::brm() and onward to rstan::stan(), which

ultimately performs the MCMC sampling. Here, we also pass

init_r = 0.5 which ensures that the random start values are

drawn from a uniform distribution ranging from -0.5 to 0.5 (instead of

the default -2 to 2). Our testing has shown that with

init_r = 0.5 MPT models with random-effect terms are much

less likely to fail initialisation. We could pass further arguments such

as chains, warmup, iter, or

thin to control the MCMC sampling.

Note that fitting this model can take up to an an hour or longer (depending on your computer).

fit_skk <- mpt(u2htm_formula, data = skk13,

tree = "type",

init_r = 0.5

)

#> Warning: Bulk Effective Samples Size (ESS) is too low, indicating posterior means and medians may be unreliable.

#> Running the chains for more iterations may help. See

#> https://mc-stan.org/misc/warnings.html#bulk-ess

#> Warning: Tail Effective Samples Size (ESS) is too low, indicating posterior variances and tail quantiles may be unreliable.

#> Running the chains for more iterations may help. See

#> https://mc-stan.org/misc/warnings.html#tail-essStep 4: Post-Processing

mptstan uses brms::brm() for model

estimation and returns a brmsfit object. As a consequence,

the full post-processing functionality of brms and

associated packages is available (e.g., emmeans,

tidybayes). However, for the time being

mptstan does not contain many MPT-specific post-processing

functionality with the exception of mpt_emmeans as

introduced below. Thus, the brms post-processing

functionality is mostly what is available. Whereas this functionality is

rather sophisticated and flexible, it is not always perfect for MPT

models with many parameters.

When inspecting post-processing output from brms, the

most important thing to understand is that brms does not

label the first parameter in a model (i.e., as shown in the model

object). For example, the model parameter Intercept refers

to the intercept of the first MPT model parameter (i.e., Dn

in the present case). All other parameters are labelled with the

corresponding MPT model parameter name, but not the first MPT model

parameter.

The default summary() method for brms

objects first lists the estimates for the random-effects terms and then

the estimates of the fixed-effects regression coefficients. As mentioned

in the previous paragraphs, all estimates have a label clarifying which

MPT model parameter they refer to with the exception of estimates

referring to the first MPT model parameter, here Dn.

summary(fit_skk)

#> Family: mpt

#> Links: mu = probit; Do = probit; g1x = probit; g2x = probit

#> Formula: resp ~ race + (race | p | id) + (1 | i | stim)

#> Do ~ race + (race | p | id) + (1 | i | stim)

#> g1x ~ race + (race | p | id) + (1 | i | stim)

#> g2x ~ race + (race | p | id) + (1 | i | stim)

#> Data: structure(list(id = structure(c(1L, 1L, 1L, 1L, 1L (Number of observations: 8400)

#> Draws: 4 chains, each with iter = 2000; warmup = 1000; thin = 1;

#> total post-warmup draws = 4000

#>

#> Multilevel Hyperparameters:

#> ~id (Number of levels: 42)

#> Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat

#> sd(Intercept) 0.78 0.18 0.48 1.20 1.01

#> sd(race1) 0.11 0.09 0.00 0.33 1.01

#> sd(Do_Intercept) 0.56 0.09 0.41 0.75 1.00

#> sd(Do_race1) 0.09 0.05 0.01 0.21 1.01

#> sd(g1x_Intercept) 1.06 0.15 0.81 1.41 1.00

#> sd(g1x_race1) 0.15 0.05 0.07 0.25 1.00

#> sd(g2x_Intercept) 0.54 0.09 0.38 0.74 1.00

#> sd(g2x_race1) 0.24 0.06 0.14 0.36 1.00

#> cor(Intercept,race1) -0.04 0.33 -0.66 0.62 1.00

#> cor(Intercept,Do_Intercept) 0.44 0.17 0.07 0.73 1.00

#> cor(race1,Do_Intercept) -0.07 0.32 -0.64 0.59 1.00

#> cor(Intercept,Do_race1) 0.05 0.29 -0.53 0.60 1.00

#> cor(race1,Do_race1) -0.06 0.33 -0.66 0.58 1.00

#> cor(Do_Intercept,Do_race1) 0.19 0.30 -0.44 0.71 1.00

#> cor(Intercept,g1x_Intercept) -0.02 0.21 -0.41 0.41 1.01

#> cor(race1,g1x_Intercept) -0.02 0.33 -0.65 0.62 1.02

#> cor(Do_Intercept,g1x_Intercept) 0.02 0.16 -0.30 0.35 1.01

#> cor(Do_race1,g1x_Intercept) -0.21 0.28 -0.66 0.41 1.00

#> cor(Intercept,g1x_race1) -0.17 0.24 -0.62 0.33 1.00

#> cor(race1,g1x_race1) -0.06 0.32 -0.66 0.56 1.00

#> cor(Do_Intercept,g1x_race1) 0.26 0.21 -0.18 0.66 1.00

#> cor(Do_race1,g1x_race1) -0.02 0.31 -0.61 0.58 1.00

#> cor(g1x_Intercept,g1x_race1) 0.28 0.25 -0.26 0.71 1.00

#> cor(Intercept,g2x_Intercept) -0.43 0.19 -0.77 -0.02 1.01

#> cor(race1,g2x_Intercept) 0.04 0.32 -0.58 0.64 1.00

#> cor(Do_Intercept,g2x_Intercept) 0.02 0.18 -0.32 0.38 1.00

#> cor(Do_race1,g2x_Intercept) 0.03 0.29 -0.54 0.59 1.00

#> cor(g1x_Intercept,g2x_Intercept) 0.19 0.19 -0.20 0.52 1.01

#> cor(g1x_race1,g2x_Intercept) 0.25 0.24 -0.22 0.69 1.00

#> cor(Intercept,g2x_race1) 0.32 0.21 -0.14 0.69 1.00

#> cor(race1,g2x_race1) 0.12 0.34 -0.55 0.71 1.01

#> cor(Do_Intercept,g2x_race1) 0.16 0.19 -0.23 0.52 1.00

#> cor(Do_race1,g2x_race1) 0.15 0.30 -0.47 0.69 1.01

#> cor(g1x_Intercept,g2x_race1) 0.13 0.21 -0.29 0.53 1.00

#> cor(g1x_race1,g2x_race1) -0.16 0.27 -0.65 0.38 1.00

#> cor(g2x_Intercept,g2x_race1) -0.12 0.22 -0.54 0.32 1.00

#> Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

#> sd(Intercept) 1114 1903

#> sd(race1) 862 2017

#> sd(Do_Intercept) 1601 2373

#> sd(Do_race1) 608 1192

#> sd(g1x_Intercept) 1769 2106

#> sd(g1x_race1) 1927 1821

#> sd(g2x_Intercept) 776 1791

#> sd(g2x_race1) 808 1606

#> cor(Intercept,race1) 3807 2430

#> cor(Intercept,Do_Intercept) 1042 1701

#> cor(race1,Do_Intercept) 423 898

#> cor(Intercept,Do_race1) 3241 2495

#> cor(race1,Do_race1) 1350 2299

#> cor(Do_Intercept,Do_race1) 2825 2447

#> cor(Intercept,g1x_Intercept) 457 1061

#> cor(race1,g1x_Intercept) 192 301

#> cor(Do_Intercept,g1x_Intercept) 998 1948

#> cor(Do_race1,g1x_Intercept) 416 586

#> cor(Intercept,g1x_race1) 2180 2803

#> cor(race1,g1x_race1) 686 1955

#> cor(Do_Intercept,g1x_race1) 3188 3305

#> cor(Do_race1,g1x_race1) 1255 2886

#> cor(g1x_Intercept,g1x_race1) 3506 3328

#> cor(Intercept,g2x_Intercept) 768 1832

#> cor(race1,g2x_Intercept) 595 1128

#> cor(Do_Intercept,g2x_Intercept) 1788 2546

#> cor(Do_race1,g2x_Intercept) 935 1664

#> cor(g1x_Intercept,g2x_Intercept) 810 2139

#> cor(g1x_race1,g2x_Intercept) 1410 2385

#> cor(Intercept,g2x_race1) 1072 1867

#> cor(race1,g2x_race1) 418 1189

#> cor(Do_Intercept,g2x_race1) 2379 3131

#> cor(Do_race1,g2x_race1) 727 1226

#> cor(g1x_Intercept,g2x_race1) 1181 2442

#> cor(g1x_race1,g2x_race1) 1710 2484

#> cor(g2x_Intercept,g2x_race1) 1510 2899

#>

#> ~stim (Number of levels: 200)

#> Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat

#> sd(Intercept) 0.88 0.14 0.63 1.20 1.00

#> sd(Do_Intercept) 0.43 0.06 0.33 0.55 1.01

#> sd(g1x_Intercept) 0.06 0.04 0.00 0.15 1.00

#> sd(g2x_Intercept) 0.42 0.06 0.30 0.55 1.01

#> cor(Intercept,Do_Intercept) 0.31 0.17 -0.01 0.63 1.01

#> cor(Intercept,g1x_Intercept) -0.15 0.39 -0.82 0.65 1.00

#> cor(Do_Intercept,g1x_Intercept) -0.25 0.40 -0.88 0.62 1.00

#> cor(Intercept,g2x_Intercept) -0.43 0.22 -0.81 -0.01 1.01

#> cor(Do_Intercept,g2x_Intercept) -0.05 0.19 -0.39 0.32 1.02

#> cor(g1x_Intercept,g2x_Intercept) -0.07 0.41 -0.79 0.75 1.02

#> Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

#> sd(Intercept) 1215 1861

#> sd(Do_Intercept) 819 1611

#> sd(g1x_Intercept) 971 1892

#> sd(g2x_Intercept) 436 1067

#> cor(Intercept,Do_Intercept) 423 913

#> cor(Intercept,g1x_Intercept) 2908 2313

#> cor(Do_Intercept,g1x_Intercept) 2597 2648

#> cor(Intercept,g2x_Intercept) 296 773

#> cor(Do_Intercept,g2x_Intercept) 507 1200

#> cor(g1x_Intercept,g2x_Intercept) 119 279

#>

#> Regression Coefficients:

#> Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

#> Intercept -0.55 0.22 -1.00 -0.17 1.01 746 1605

#> Do_Intercept 0.14 0.11 -0.08 0.35 1.01 839 1780

#> g1x_Intercept -1.35 0.17 -1.71 -1.01 1.00 1420 2100

#> g2x_Intercept -0.38 0.12 -0.62 -0.15 1.00 852 2367

#> race1 0.37 0.12 0.15 0.60 1.00 1312 2034

#> Do_race1 0.01 0.05 -0.09 0.11 1.00 1775 2505

#> g1x_race1 -0.06 0.04 -0.15 0.03 1.00 2877 3014

#> g2x_race1 -0.13 0.07 -0.27 0.01 1.00 1264 2532

#>

#> Draws were sampled using sampling(NUTS). For each parameter, Bulk_ESS

#> and Tail_ESS are effective sample size measures, and Rhat is the potential

#> scale reduction factor on split chains (at convergence, Rhat = 1).Typically the primary interest is in the fixed-effect regression coefficients which can be found in the table labelled “Regression Coefficients”. Some of these estimates are smaller than zero or larger than one, which is not possible for MPT parameter estimates (which are on the probability scale). The reason for such values is that the estimates are shown on the unconstrained or linear – that is, probit – scale.

Looking at the table of regression coefficients we see two different

types of estimates for each of the four MPT model parameters, four

intercepts and four slopes for the effect of race (recall that estimates

without a parameter label are for the Dn parameter). When

inspecting the four slopes in more detail we can see that only for one

of the slopes, the race1 coefficient for the

Dn parameter, does the 95% CI not include 0. This indicates

that there is evidence that Dn differs for the two

different types of face stimuli (i.e., German versus Arabic faces). This

finding is in line with the results reported in Singmann et al. (2013).

Hence, even though the table of regression coefficients is on the probit

scale, we can in situations such as the present one still derive

meaningful conclusions from it.

One way to obtain the estimates on the MPT parameter scale is by

using package emmeans. mptstan comes with a

convenience wrapper to emmeans, called

mpt_emmeans(), which provides output for each MPT model

parameter simultaneously but otherwise works exactly like the

emmeans() function:

mpt_emmeans(fit_skk, "race")

#> parameter race response lower.HPD upper.HPD

#> 1 Dn german 0.43305661 0.24889660 0.5938111

#> 2 Dn arabic 0.18455338 0.06265918 0.3093766

#> 3 Do german 0.56213484 0.46394103 0.6510327

#> 4 Do arabic 0.55176900 0.46281825 0.6424701

#> 5 g1x german 0.08032168 0.03225784 0.1407091

#> 6 g1x arabic 0.09857215 0.04504090 0.1602572

#> 7 g2x german 0.30406461 0.20843582 0.4077200

#> 8 g2x arabic 0.39994499 0.30632449 0.5048775We can also use the special syntax "1" to get the

overall mean estimate for each parameter. Note that, because of the

non-linear probit transformation, this might be different from the means

of the marginal means.

mpt_emmeans(fit_skk, "1")

#> parameter X1 response lower.HPD upper.HPD

#> 1 Dn overall 0.29757056 0.15962015 0.4325167

#> 2 Do overall 0.55653868 0.47342278 0.6399529

#> 3 g1x overall 0.08928845 0.04009512 0.1488125

#> 4 g2x overall 0.35150225 0.26724324 0.4370866Another MPT model specific function is ppp_test(), which

calculate a posterior predictive

-value

to test a model’s fit. More specifically, the function currently

implements the T1-test statistic of Klauer (2010). If the

-value

is small, say smaller than .05, this indicates an insufficient fit or

model misfit – in other words, a significant divergence of the observed

data from the data that would be expected to arise if the fitted model

were the data generating model.

In the present case the -value is clearly large (i.e., near .5) indicating an adequate model fit. Given that the unsure-extended 2-high threshold model is a saturated MPT model (with number of parameters equal to number of independent categories), such a good fit is probably not too surprising.

ppp_test(fit_skk)

#> ## Mean structure (T1):

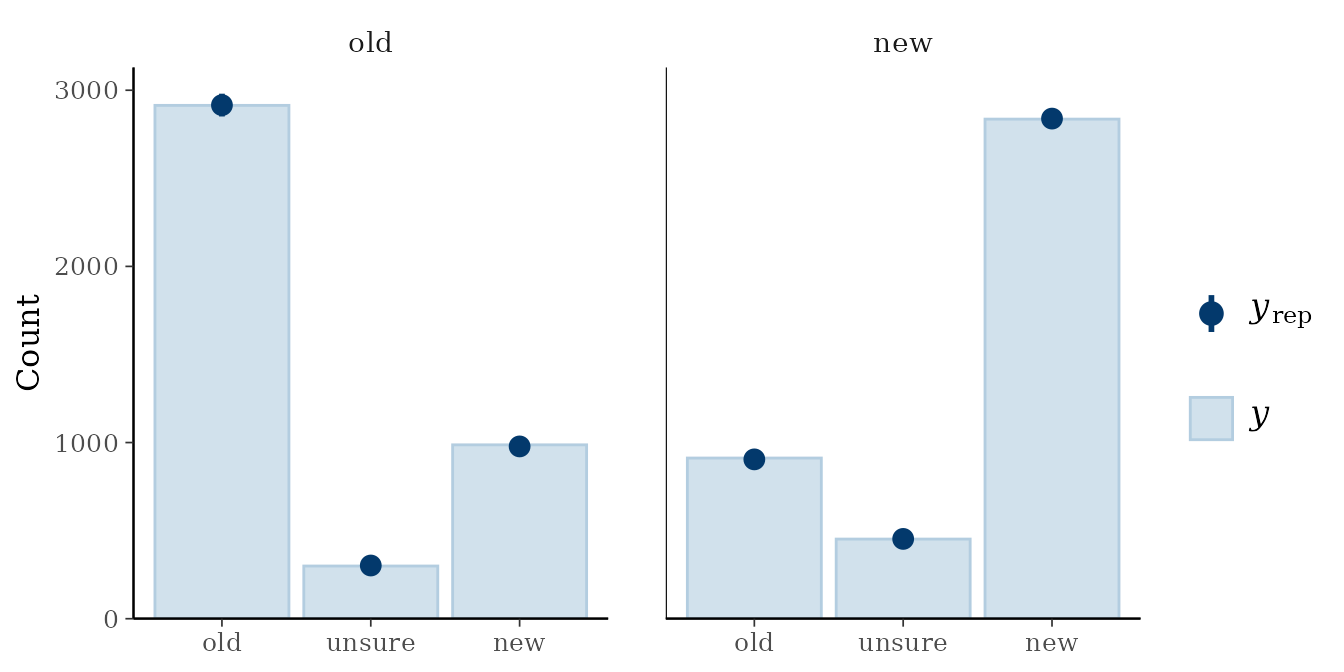

#> Observed = 3.293324 ; Predicted = 3.210767 ; p-value = 0.491As mentioned above, mptstan also provides full

integration for brms post-processing.

For example, we can obtain graphical posterior predictive checks

using pp_check(). For MPT models,

type = "bars_grouped" provides a helpful plot if we

additional pass group = "mpt_tree" (which creates one panel

per tree). We can also change the x-axis labels to match the response

categories.

pp_check(fit_skk, type = "bars_grouped", group = "mpt_tree", ndraws = 100) +

ggplot2::scale_x_continuous(breaks = 1:3, labels = c("old", "unsure", "new"))

#> Scale for x is already present.

#> Adding another scale for x, which will replace the existing scale. In addition, we can directly obtain information criteria such as loo or

get posterior mean/expectation predictions for each observation.

In addition, we can directly obtain information criteria such as loo or

get posterior mean/expectation predictions for each observation.

(loo_model <- loo(fit_skk))

#>

#> Computed from 4000 by 8400 log-likelihood matrix.

#>

#> Estimate SE

#> elpd_loo -5678.4 63.0

#> p_loo 459.7 7.7

#> looic 11356.8 126.0

#> ------

#> MCSE of elpd_loo is 0.4.

#> MCSE and ESS estimates assume MCMC draws (r_eff in [0.4, 1.8]).

#>

#> All Pareto k estimates are good (k < 0.7).

#> See help('pareto-k-diagnostic') for details.

pepred <- posterior_epred(fit_skk)

str(pepred) ## [sample, observation, response category]

#> num [1:4000, 1:8400, 1:3] 0.367 0.413 0.381 0.364 0.496 ...Priors

mptstan comes with default priors for the fixed-effect

regression coefficients. For the intercepts, it uses a Normal(0, 1)

prior and for all non-intercept coefficients (i.e., slopes) Normal(0,

0.5) prior. These priors can be changed through the

default_prior_intercept and default_prior_coef

arguments (see ?mpt).

For the hierarchical structure, mptstan uses the

brms default priors.

References

- Klauer, K. C. (2010). Hierarchical Multinomial Processing Tree Models: A Latent-Trait Approach. Psychometrika, 75(1), 70-98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11336-009-9141-0

- Rouder, J. N., Morey, R. D., Speckman, P. L., & Province, J. M. (2012). Default Bayes factors for ANOVA designs. Journal of Mathematical Psychology, 56(5), 356–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmp.2012.08.001

- Singmann, H., Kellen, D., & Klauer, K. C. (2013). Investigating the Other-Race Effect of Germans towards Turks and Arabs using Multinomial Processing Tree Models. In M. Knauff, M. Pauen, N. Sebanz, & I. Wachsmuth (Eds.), Proceedings of the 35th Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society (pp. 1330–1335). Austin, TX: Cognitive Science Society. http://singmann.org/download/publications/SKK-CogSci2013.pdf